Advertisement

Some East Boston Residents Are Wary Of Proposed Electrical Substation

Resume

This story can also be read in Spanish.

A proposed electrical substation in the Eagle Hill area of East Boston has drawn protest from residents worried about flood risk and safety.

Eversource wants to build the substation in a flood-prone area near Chelsea Creek, across the street from a popular playground and near tanks of jet fuel for Logan Airport. The utility says the project poses little risk to the public, but because substations can catch fire and explode, some local residents are trying to stop it.

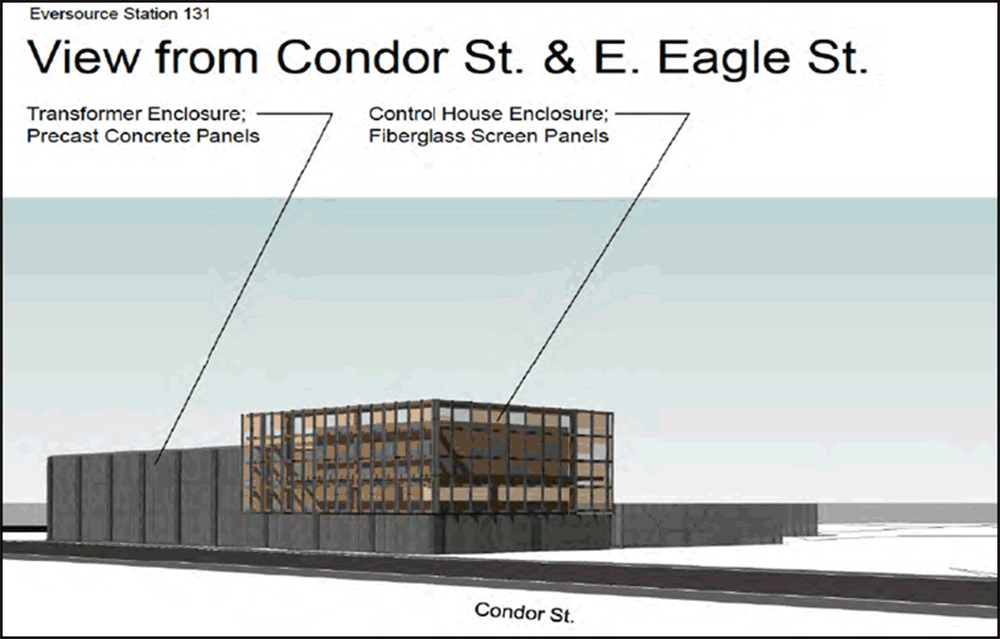

Electrical substations are a critical part of our energy landscape, converting high-voltage electricity to a lower voltage so you can use it in your house. They’re usually built behind a tall fence or wall, and look like a network of metal towers, latticed structures and wires.

New England has about 900 substations connected to high-voltage transmission lines, and Eversource says building one in East Boston is necessary to meet the area’s growing electricity demands.

“Right now, the East Boston, Chelsea, Lynn, Revere area is served out of the Chelsea substation, but that substation is at its maximum capacity,” says Bob Clarke, Eversource's director of siting and project outreach. “We do have significant load growth in this area, and to meet that load growth, we need additional substation capacity.”

While some people question Eversource’s energy demand forecast, most people opposed to the project are worried about safety, and opposed to building more infrastructure in an area already burdened with heavy industry. They are also frustrated by what they say has been a lack of transparency and public input during the siting process.

“Between the jet fuel, the noise pollution, the air pollution from the airport, the salt mounds across the creek — this community has had the burden of so many environmental hazards and injustices for quite some time,” says Paul Kozak, a local resident who lives with his wife and three young children in a house a few hundred feet from the proposed substation. “And instead of asking the public how we could best use the space, or how we envision that space being used, we’ve just had to sit back and accept [that] the substation from Eversource is going to be there.”

Why Build Here?

When the company first proposed the project to the state in 2014, it knew where it wanted to put it: the small parcel of land Eversource owns inside a larger city-owned property.

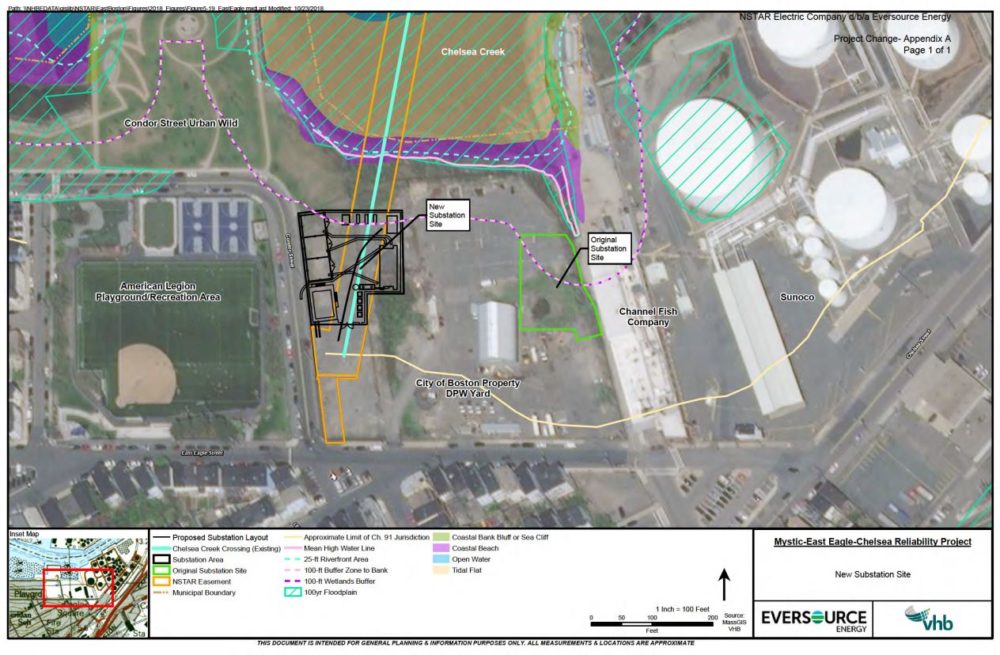

338 East Eagle St. is an overgrown and mostly empty lot sandwiched between the base of a densely populated hill and Chelsea Creek. American Legion Playground — a popular park known as the City Yards — is to the west. And to the east is the Channel Fish Company, a family owned East Boston seafood processing business that’s been around since 1962.

“We didn’t look at a lot of other areas because we had the available land," and real estate is limited in the area, Eversource's Clarke says. “This is a good location for this station. Are we saying it’s perfect? There’s no perfect location.”

Shortly after Eversource formally proposed the project, the owner of the Channel Fish Company, Louis Silvestro, began voicing his opposition. He placed signs and placards around the neighborhood, and successfully petitioned for intervenor status with the Energy Facilities Siting Board (EFSB), the state agency in charge of permitting big energy infrastructure.

The substation was going to be about 18 feet away from the fish processing plant, and Silvestro was concerned about electromagnetic radiation from the substation interfering with sensitive equipment.

The siting board held hearings with Channel Fish and Eversource in 2016, and issued a final decision in November 2017. The board approved the project with the condition that Eversource and the city of Boston consider moving the substation to the other side of the property, farther from Channel Fish — but closer to the popular playground and often-flooded street corner. The city agreed to the land swap, and the siting board is now considering whether to approve the change.

While this decision satisfied Channel Fish, some residents of East Boston were furious.

"Anywhere on that property we think is a bad idea because the entire property abuts Chelsea Creek,” says John Walkey, an East Boston resident and waterfront initiative coordinator at GreenRoots, a Chelsea-based environmental nonprofit leading the fight against the substation. “It just seems like it’s a project that’s totally antithetical to the mayor’s plans for the coast.”

The Flood Risk

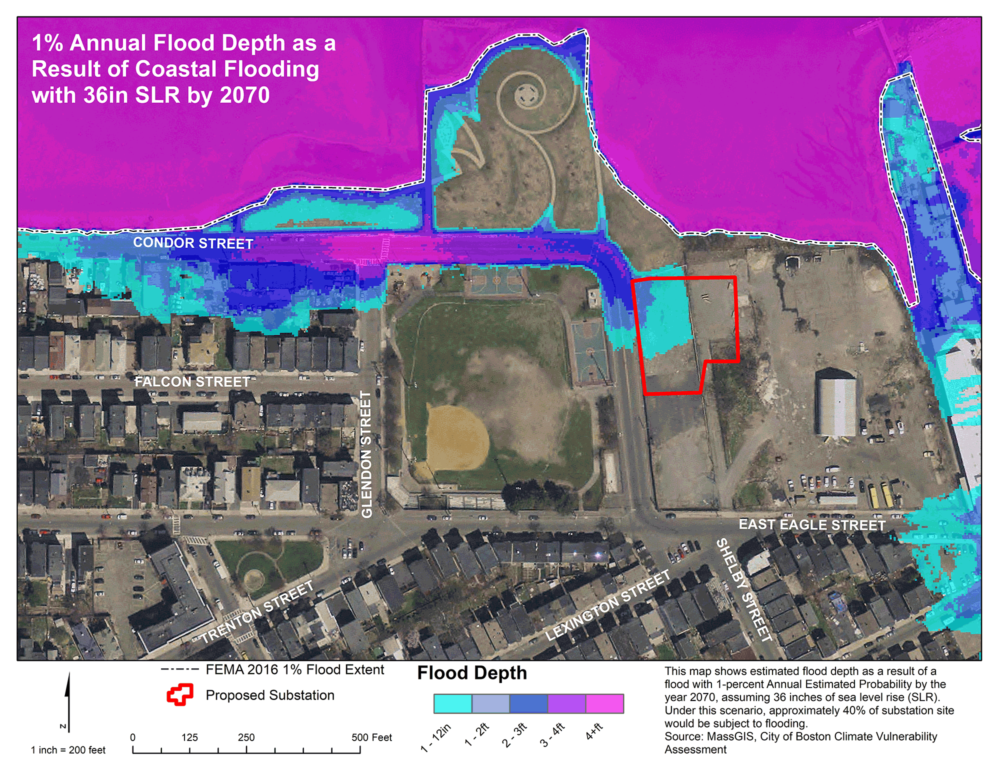

East Boston is the city’s poster child for climate-induced flooding, which is partly why Marcos Luna, a local resident and professor in the Geography and Sustainability Department of Salem State University, calls the substation project “short-sighted.”

“When I looked just briefly at the maps of the area, I saw that it’s right in an area that’s likely to be flooded,” he says. “And with the city’s Climate Ready Boston report, there’s heightened sensitivity to all these potential areas that could be affected by water, and different efforts to make the city more resilient. So putting electrical infrastructure in an area that’s likely to flood seemed really counter to all those efforts.”

In emails, city officials say the proposal meets the city’s climate resiliency standards, while also emphasizing that Boston has no jurisdiction over the project.

Eversource says it’s building the substation outside of the 100-year and 500-year flood zones, but Luna isn’t sure that's enough. As sea level rises, the 100-year and 500-year flood lines move further inland, he says.

Luna sits on the board of GreenRoots and offered to model the potential for flooding with Geographic Information System (GIS) software. His maps are based on data from the city, and demonstrate what could happen to the property under different sea level rise and storm surge scenarios in the future.

One map shows that if the seas rise 21 inches by 2050 — a likely scenario — a 100-year storm will flood much of Condor Street and the Chelsea Creek shoreline, but stop short of the substation property. Yet a similar storm in 2070 with 36 inches of sea level rise — also likely — could put parts of the site under a foot or more of water.

Eversource says the base of the substation would be high enough to protect against sea level rise, and according to Luna's maps, the substation should be OK in all but the most extreme scenarios — a severe hurricane, for example. But given the likely lifespan of the substation, he says the company should be planning for events like a hurricane, in addition to 10 feet of sea level rise.

"My critique is that Eversource has not adequately accounted for sea level rise over the likely life of the structure at that site and is not taking into account the likely range of possibilities," Luna says. "They should be using probable, high-end or worst-case scenarios because this substation is 'essential infrastructure' according to their own documentation."

What's more, he says, "none of this flood risk modeling takes into account the role of storm water flooding due to intense rain and backed-up sewers."

GIS maps of flooding caused by sudden heavy rainstorms are not always accurate because modeling these scenarios requires huge amounts of granular data about street grade, sewer capacity and ground cover on every block. While the Boston Water and Sewer Commission is currently gathering some of this information, Luna says the existing data isn’t particularly sophisticated.

The part of Condor Street near the proposed substation already floods a few times a year during heavy rainstorms, and the problem is likely to only get worse because of climate change.

“You’re basically putting infrastructure in harm’s way when you know things are going to get bad in that location,” Luna says.

Fire Risk

Flooding isn’t the only reason people in the neighborhood oppose the substation. They’re worried about kids climbing the fence and getting electrocuted. They’re worried about aesthetics. And they’re worried about what could happen if the station caught fire. There are tanks of jet fuel about 800 feet away.

“These substations have caught on fire before,” local resident Kozak says, pointing out that during Hurricane Sandy, a Manhattan substation caught fire and exploded, turning the sky bright green. And just this past year, substations caught fire and exploded in Queens, New York, and Madison, Wisconsin.

“[What] if that happens here and there’s a gust of wind?” he continues. “Putting a substation near such amounts of jet fuel is risky.”

But Clarke of Eversource says the company is in compliance with national electric safety standards, so fire shouldn't be a problem.

"We have redundant protection systems that would interrupt the power flow before a fire would start. And in the event that there was a fire, we have fire suppression systems," he says. "We’re meeting all required standards and more."

Environmental Justice

Some residents also oppose the project on environmental justice grounds. Eagle Hill is a working-class area with a large immigrant population, and many who live there feel that when it comes to the substation, they were excluded or ignored.

“This project is a typical environmental justice story," says resident Walkey. "You take a low-income neighborhood, and someone comes in and says we’re going to put in this dicey sort of substation. These are the kinds of things that benefit the region as a whole, and yet the burden that they represent is only held by a certain community."

While Clarke of Eversource says the company made a strong effort to do public outreach, Walkey says it clearly didn’t work. At a siting board meeting held earlier this year at East Boston High School, many residents said they had no idea this project was in the works until a community organizer knocked on their door. Others lamented the lack of translation services at a previous siting board meeting or said they thought the city had promised to turn the plot of land into a soccer field or park with access to Chelsea Creek.

“We have a lack of open space and what you're proposing to do is put a substation in an area the city promised a soccer field,” community member Heather O’Brien said at the meeting. “It seems ludicrous that this is the only place to put this — in an environmental justice community that's already overburdened with hazards. The community has had enough. We don't need it, we don't want it and we don't deserve it.”

What Happens Next?

The final decision now rests with the state EFSB. While the board is specifically looking at the impacts of moving the station to the new spot on the property, Walkey of GreenRoots says his organization is trying to open an inquiry into whether the substation is needed at all.

The board is expected to make a decision later this year.

In the meantime, Walkey says, "we’ll be working on the ground with the community to continue educating people, to continue mobilizing them, and to continue putting pressure on elected officials.”

This segment aired on August 22, 2019.